In the landscape of Italian cinema in the second half of the twentieth century, few names have managed to intertwine civic engagement with the evocative power of cinematic storytelling as coherently – both ethically and aesthetically – as Paolo and Vittorio Taviani. Shy, reserved authors who remained distant from the spotlight of cultural celebrity, yet deeply engaged in the profound debate on identity, memory, and the meaning of narration, the Taviani brothers created a body of work that is both cohesive and surprisingly multifaceted, moving through history and myth, the real and the dreamlike, the individual and the collective.

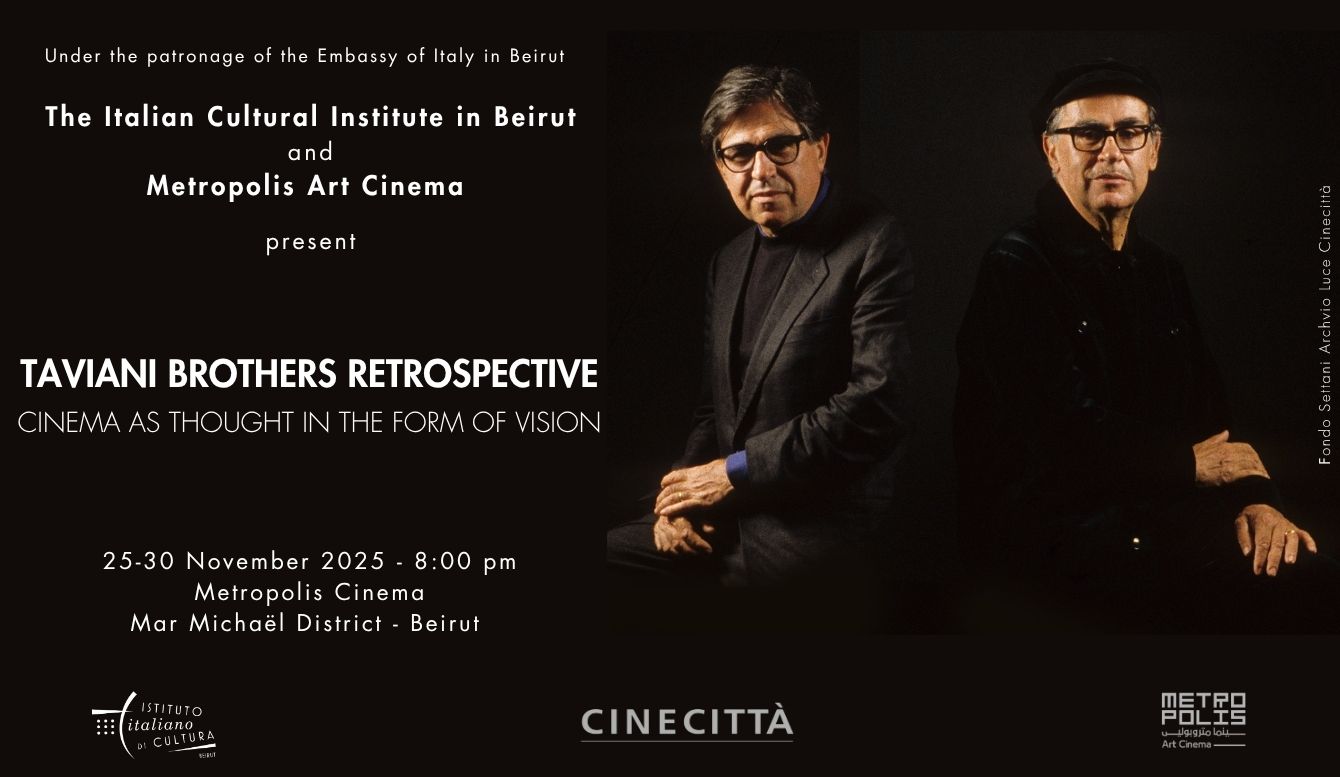

This retrospective presents six fundamental milestones from an artistic journey spanning over fifty years, covering the various seasons of their cinema, from their early international successes to Paolo’s final, poignant solo testament. It is thus an invitation to enter a unique poetic universe, where the rigor of staging coexists with the freedom of invention, and where every shot seems to pose a question about the meaning of reality and representation.

“Padre padrone“ (1977) – Palme d’Or at Cannes – marked the public explosion of their cinema: the story of linguistic and cultural emancipation of young Gavino Ledda, adapted from his autobiographical novel, becomes a paradigm of an Italy torn between atavism and modernity, between authority and individual consciousness. Shot with non-professional actors and structured with a rigorous dialectical approach, the film is a rare example of pedagogical cinema that never descends into rhetoric, but instead elevates personal experience to a universal form of liberation.

“Allonsanfàn“ (1979), starring an intense Marcello Mastroianni, marks a return to history with a disenchanted and deeply political sensibility. Through the figure of a weary and skeptical former revolutionary, the Taviani brothers reflect on utopia and betrayal, on the tension between ideals and compromise, portraying the Italian Risorgimento as a season both noble and fragile. The very title – an infantilized revolutionary slogan – reveals the tragic awareness of a disintegrating political dream.

“La notte di San Lorenzo“ (1982) is perhaps their absolute masterpiece: a choral tale set during the days of the Liberation, where the realism of the historical context coexists with a fable-like tone. The child’s point of view and the almost epic structure give the film a suspended tone in which horror and beauty coexist. It is a work about memory and the transmission of trauma, but also about everyday heroism and the hope that survives through storytelling.

“Kaos“ (1984), based on Pirandello, is a work of great expressive and visual freedom. Here, the Tavianis reach one of the heights of their art, merging literature with the grammar of cinema: four Sicilian tales plus an epilogue, performed with grace, irony, and depth, create a fresco of the Mediterranean soul where death, time, solitude, and the sense of identity blend into a timeless vision, suspended between reality and metaphysics.

After years of apparent silence, the Tavianis returned in 2012 with “Cesare deve morire“, winner of the Golden Bear in Berlin. Filmed inside the Rebibbia prison with inmate-actors, the film stages Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, creating a dual level of fiction and truth that mirror and amplify each other. It is a work that questions the meaning of representation, guilt, freedom, and theatre as a salvific space. The stark and powerful black-and-white conveys an essential cinema still capable of striking insight.

Finally, “Leonora Addio“ (2022) – directed by Paolo Taviani after the death of his brother Vittorio – closes the circle with a reflection on mourning, disappearance, and the very possibility of storytelling. Inspired by the story of Pirandello’s ashes and one of his short stories, the film is a moving homage not only to the Sicilian writer, but also to the lost brother, the cinema they shared, and to art as resistance against dissolution. It is the final and necessary gesture of an author who has always believed in storytelling as a form of knowledge and survival.

This retrospective thus aims to highlight not only the cinematic value of one of the most influential and original directing duos in the history of Italian cinema, but also the intellectual and moral legacy of a body of work that succeeded in combining thought with image, history with vision, word with poetry.